St James’s Gate Cooperage

Coopering is the traditional craft of making wooden casks, these wooden casks were used to ship Guinness from the brewery site in Dublin all over the world for almost 200 years. The skilled workers who made the casks were known as ‘coopers’ and Guinness had its own cooperage onsite to facilitate their work. The scale of the Guinness brewery required a large workforce, with half of Dublin’s coopers working for the site in the 1920s.

Constructing Perfection

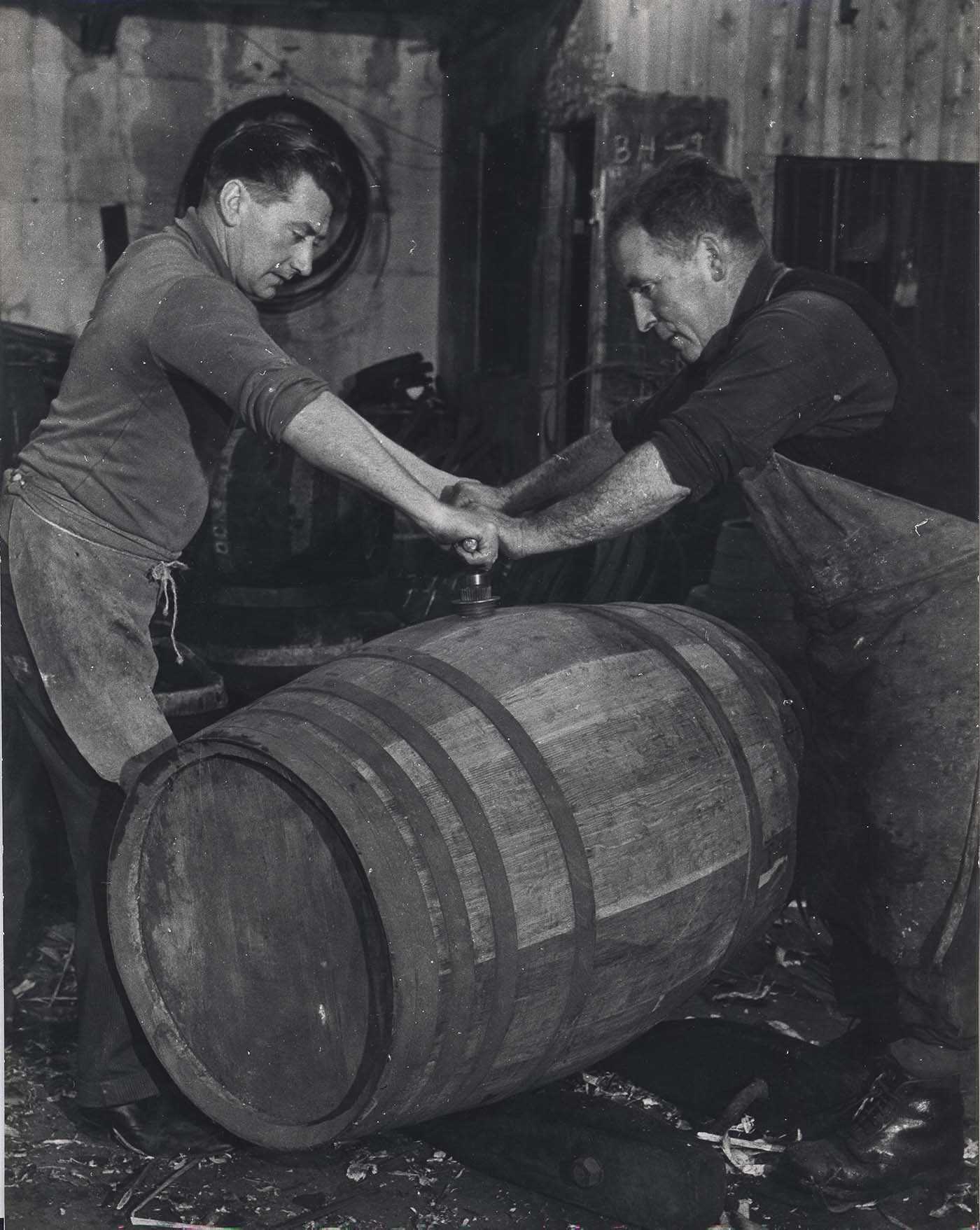

Coopering was a physically demanding process, conducted entirely by hand. Coopers might employ upwards of 30 tools to make a single cask. The casks comprised wooden staves and metal hoops which were precisely shaved and cut to fit together – no adhesives were used in the process. The casks were airtight, strong enough to withhold the force of fermenting beer and durable to withstand years of rough handling. Coopering demanded considerable skill with applicants undergoing a rigorous apprenticeship that could last up to seven years.

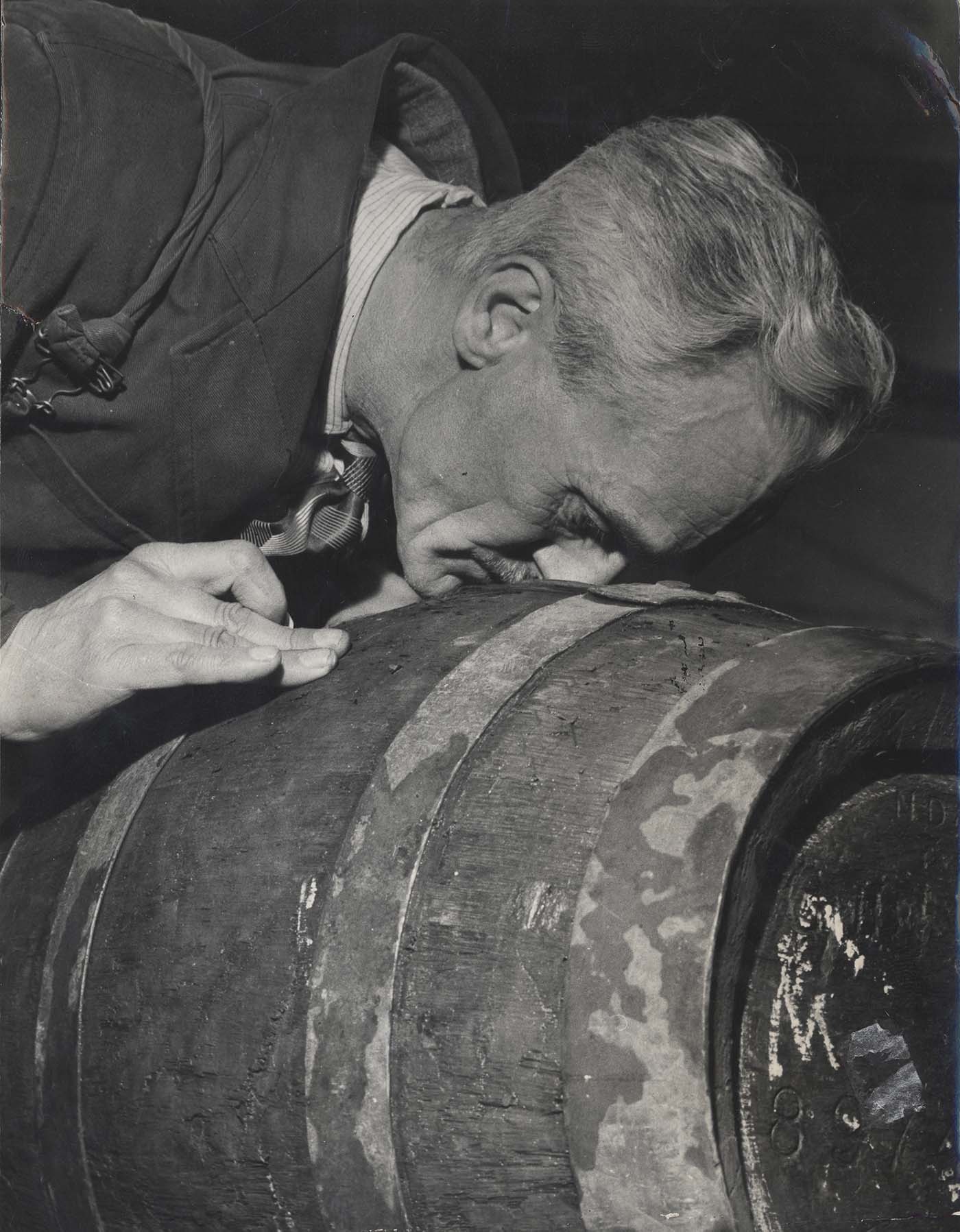

Sticking their Nose In

Casks were not single use and coopers conducted repairs on and cleaned any returned casks that may have been damaged or that acquired a foul smell from lying idle for too long. Some coopers were specially appointed as ‘smellers’ to weed out these foul-smelling casks for treatment.

Dressed to Skill

Guinness coopers would have worn a rough worn suit (jacket, trousers and waistcoat), white shirt, sturdy workmen’s boots and flat cap. They would have their sleeves rolled up when in the process of making a cask and would have worn a protective apron.

A Generational Craft

Coopering was a ‘closed trade’ meaning that it was passed down the male line from generation to generation within the same family. This meant that many coopers working on the brewery site would have identical names. Many of the coopers were given nicknames to distinguish between individuals. Notable examples include ‘Tapeworm’ Murphy, ‘Electric’ McMullen, ‘The Sheriff’ McMullen and ‘General’ Ryan.

The Final Guinness Coopers

The twentieth century heralded the end of the cooperage at Guinness. Aluminium kegs were introduced after the Second World War in 1946. Both the wooden and new metal casks were used concurrently for a time. The last wooden cask was filled at St James’s Gate in March 1963.