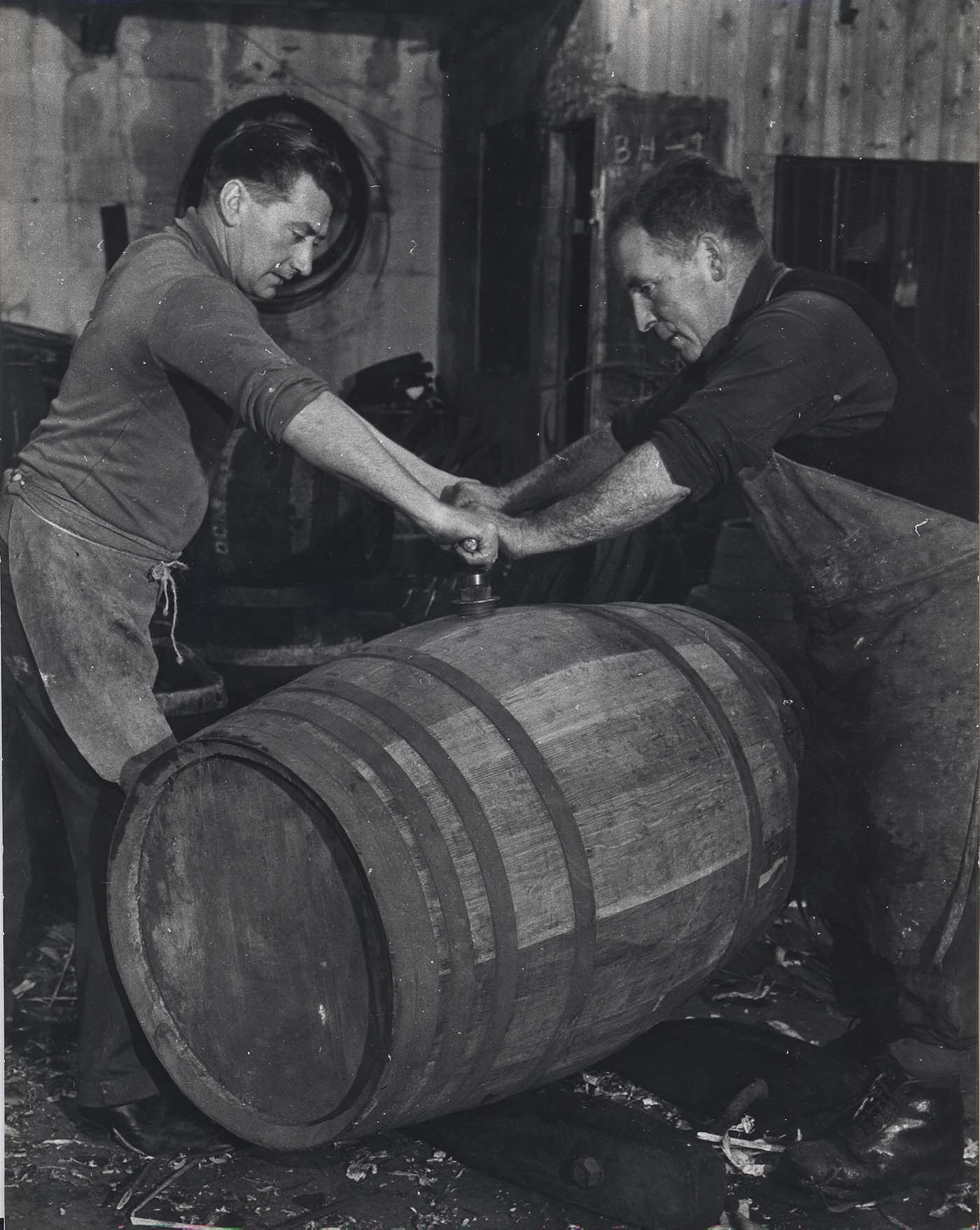

During the late 1800s, a period of economic uncertainty, Guinness was both the biggest and one of the most sought-after employers in Ireland. Guinness employees benefited not just from job security and a salary consistently 10-20% higher than the Dublin average, but an employer with the interests of their employees at the forefront of their practices. Before old age payments were introduced by the State, Guinness was paying employees pensions including stipends to widows and orphans of former employees. Additionally, a cooper at Guinness would have enjoyed free healthcare from 1870 onwards when the first medical centre was established on the premises of St. James’s Gate Brewery. The cooper, along with his family, would have been entitled to free treatment at the medical centre, a benefit which would continue throughout their retirement. Should the worst befall, the cooper’s family would also have received a grant for his funeral – an often-crippling expense for most of the working-class families in Dublin at the time.

After a hard day’s work in the cooperage, a cooper could partake in one of the many societies funded by the company. The Guinness Athletic Union (GAU) was founded in 1903 to foster athleticism and sportsmanship among the staff and employees within the brewery. It worked a charm and soon Guinness was famous for its football and tug of war teams. By the 1960s, the sports covered by the GAU expanded to include hockey, handball, rugby, boxing, athletics, GAA, cricket, golf, swimming, table tennis, squash, and angling.